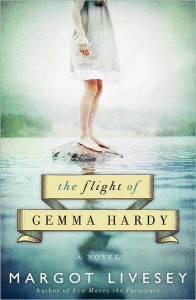

When @em_ingram walked into my cube last week and told me that I absolutely had to read The Flight of Gemma Hardy, I took it to heart. Margot Livesay’s love letter to Jane Eyre, surprised and delighted me. It’s a familiar story, not just because of the latest filmed adaptation (which I thought was excellent), but because, like so many of these great novels, these stories are embedded in our collective reading consciousness. I’ve read a number of books that write back to Brontë, and I count Jean Rhy’s Wide Sargasso Sea among one of my favourite novels, of all time.

When @em_ingram walked into my cube last week and told me that I absolutely had to read The Flight of Gemma Hardy, I took it to heart. Margot Livesay’s love letter to Jane Eyre, surprised and delighted me. It’s a familiar story, not just because of the latest filmed adaptation (which I thought was excellent), but because, like so many of these great novels, these stories are embedded in our collective reading consciousness. I’ve read a number of books that write back to Brontë, and I count Jean Rhy’s Wide Sargasso Sea among one of my favourite novels, of all time.

Ten-year-old Gemma, an orphan now twice-over, finds herself shunted away to Claypoole, where she’s a “working girl,” scrubbing floors and dusting shelves for just to sustain her Annie-like existence and meagre education. But she’s strong willed and good of heart, and lands an au pair position in the Orkneys, where her fate is forever linked with that of her employer’s, Mr. Sinclair. As with the original book, morality and secrets are the enemy of love, and Gemma finds herself chased away, yet again, from yet another home. She lands not fifty miles from her awful aunt’s house, and must come to face the truth of her own existence, her own life’s story, before she can even consider whether or not she’d like to be married. Set after the Second World War, when Scotland itself must have been changing, where the men and the women who had been through the battles faced a different world when they returned, Gemma’s life opens up for her in ways that her predecessor, Jane, would have most likely reveled in.

While I found some of the strings tying this novel to the other a bit flimsy, in the end, it didn’t matter because Gemma’s such a wonderful character in her own right. When she sets off to “find herself,” pushed to the brink by the choices forced upon her by both society and “good” morals, you root for her entirely, and that’s enough for me. Knowing the “other” Jane’s story so well becomes irrelevant by the end of the book, as if Livesay wrote herself out of it on purpose, if only to prove how far we’ve all come, to examine the roots of feminism, of free will, of delight in the power of learning, all of which, I’m sure, Brontë would have reveled in herself. Like Emma described it to me, this is a book for people who love books, and she’s not at all wrong.