September always means new beginnings for me. I can’t help but think of it as the real “new” year–school starts, the weather changes, we are knee-deep in real life that summer always provides an escape from. And yet, the last few years, September was more of the same, our same routine, a couple of days of daycare, more days off, race around on the weekend trying to get things done, and wham! it’s Christmas.

September always means new beginnings for me. I can’t help but think of it as the real “new” year–school starts, the weather changes, we are knee-deep in real life that summer always provides an escape from. And yet, the last few years, September was more of the same, our same routine, a couple of days of daycare, more days off, race around on the weekend trying to get things done, and wham! it’s Christmas.

This September, I’m meditative. I’m finally, after over four years, off the prednisone. Keep in mind it’s only been a week, but still, it’s a week without that awful drug. I’m feeling it. My bones are achy, and I’m exhausted, and then it hit me. This is life with the disease. It’s not so much a complaint, but a full and complete acceptance that the good health I had before I had my son is gone forever. I can muddle through my life, I’ve been doing it for decades. But do I want to? Of course I’m not suggesting otherwise. In the sense that I’m not about to do anything dramatic. There’s a part of life with a disease that goes unrecognized in a way. To the outside world, I look like a middle-aged mum–my hair’s greying, I’ve got extra pounds in places where there used to be smooth skin, and, more often than not, I’m with our boy. That changes the perspective. The more people you meet later in life, how you need to keep telling the stories, how you need to keep explaining.

I was at a party the other night. I rarely drink, and I rarely go to parties, but this was a work event, and it was a lot of fun. And, inevitably, some question comes up, something about having another baby (too old! too sick) that I have to explain in a couple of short sentences the almost-life-almost-death way that I exist every single day. I’m not about to keel over. The disease is in remission for the most part, but the symptoms, they remain. The exhaustion is the hardest part. The feeling old, now. The constant nagging of my lungs when I try to bike up a hill. A lot of it is being out of shape and being overweight, but a lot of it is disease too. I’m fighting all of the battles of society these days, but with a backpack full of other crap on my back. And that is life with a disease.

So. Enough complaining, whining, whinging. Whatever. I’ve made a lot of new year’s revolutions on the blog. I’ve made a lot of sentences that start with, “I’m going to change this…” and start small. And still nothing sticks. Nothing has come close to dropping an appendix and becoming the healthiest I’ve been in a decade. I don’t have another appendix. I don’t have a lot of energy. I don’t even know how to change. Except. I kind of do. I know that if I have a good pattern, I’ll continue with it–it’s not much, but flossing every day has now become a habit. Biking is hard but I’ve managed it most of the summer with the exception of having a rotten cold for a couple of weeks. But eating, that’s the hardest part to fix–I have some terrible habits, especially with breakfast, and I’m not sure how to fix them. That is, I’m not sure if I’ve got the will power to do it. It comes down to that, when you’re so tired, so so so so tired, making any kind of change is akin to biking up the biggest hill in your neighbourhood on your highest gear. I just can’t do it.

I said I would stop complaining. And I spent a whole other paragraph, well, complaining.

And so I am, here. Decades into living with a disease. At this point in my life, I’ve spent longer being sick than I’ve ever been healthy. I’ve spent more time taking medicine than not. And so you would think I would have, by this point in my life, come to terms with living with the disease. Except, I haven’t. Now I’m taking more medicine than ever, and it’s morning and night, every day, every single day until the rest of my life. And it will be now more medicine instead of less, and unless I make some changes, it will always be more medicine instead of less.

I was feeling profound when I started this post. Feeling like the experience in having the disease for so long must mean something. The search for meaning in my ill health or the struggle to overcome it all, there must be a point. Yet, the existential in me understands there’s no overriding point to any of it. It’s random, and fool-hardy of me to think otherwise. The disease is not something to be filed away like my old tax receipts. It’s something to be considered.

This month is the ten year anniversary of having my hip replaced. It’s also the ten year anniversary of blogging, well, almost–according to the blog, I actually started on February 10th, 2005–but all that time blurs for me, because the major changes in my life kicked off with my hip replacement surgery. I left my job as an Executive Producer for television websites in the fall, had my hip replaced, moved into my house, got fired, had a nervous breakdown, healed, sought therapy, survived, and found my career. Here’s the first post:

Thursday, February 10, 2005: Happy Freaking New Year!

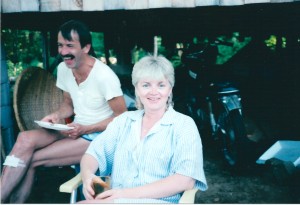

What a start to the new year! Let’s see — I had hip replacement surgery last September, so on January 1st I was still learning to walk. Then, I went back to work after being off on sick leave (you heard me: sick leave) to find out they had reorganized me right out of a job. Oh, and to add to the stress we (me and my Rock and Roll Boyfriend) had just bought a house. Of course, being a Rock and Roll Boyfriend, means he doesn’t have a steady job. In what’s supposed to be a time of renewal and regeneration, good luck and New Year’s resolutions, I’m standing on the side of the road worried I’m going to lose my new house because I’ve lost my big, fancy job and, well, frankly I’m having trouble standing up…because I just got my hip replaced.

So now, I’m temping for $13 bucks an hour trying to find a new job. Do you know anyone that’s hiring?

And, within a month or two of that post, I was working at Random House, which was a wonderful experience, being mentored by someone I still like and admire very much, and for two full years I was happy just to be in publishing (but not with the commute to Mississauga) and ended up at HarperCollins Canada, where I’ve been ever since. And in that time, I’ve almost lost my life twice–once when my appendix ruptured and no one could figure out what was going on, and then when I had my son. In the decade in between having my tragic hip be replaced, I have found my voice, written one unpublishable book (never knew I could write a novel, that’s something) and finished another that I like very much. I’ve written a bunch of abridgements, done some interesting freelance, become a teacher, have a respectable career, and a marriage, and a family.

I’ve done all of this with the disease just there, lurking, and poking, and testing, and falling up, and falling down. I’ve done it all through blood tests, and doctor’s visits, and trauma, and regular check ups. I’ve seen Paris, and London, and Ireland, and Cuba, and Mexico, and many places in Canada. I’ve seen bands I love and bands I’ve hated. I’ve read book after book and reveled in the power of the written word. I’ve blogged and then forgotten to blog. I’ve been swept away in motherhood and all it brings to your life (and takes away). I’ve celebrated anniversaries and birthdays and holidays.

And the disease has taken none of life away from me. Maybe that’s my point. Maybe I had to write it all out, everything I’ve thought about, and everything that’s given me pause over the last few weeks as I celebrate a decade being a bionic girl. I have this life. I have this life. I have this life. And it’s a gift even if it means the medicine, and the doctor’s visits, and the constant hum of the disease strumming under my bones and in my blood. I still have this life. I have a life. And I have given a life to someone else. Many things that weren’t possible on the ill-fated day the specialist came into the hospital room to visit a teenaged girl who had lived very little up until then, but been through so much. They never told me how hard it would be. Perhaps that’s a blessing in disguise. They never talked about the side effects and the ugliness inherent in the medication. And that’s a blessing too.

But I had to live with the disease to learn about how to live with a disease. In short, I had to live. And that’s okay. So if some things change this September, that’s good. If I can finally be off prednisone for a while, that’s a gift. And if I can finally understand that the point of the disease is that there’s no point to it, really, but that I’m still living, well, here’s to the next decade with my tragic hip. Here’s to another ten years of being bionic. Here’s to it.

Oh, so late. It is now two weeks passed the first of the new year, and I have not written down a single revolution for 2015. Maybe it’s for the best. To not have a Revolution in mind for the year. Still, I need organization, but I think a better phrase might be that I need simplification, simplicity, even, in 2015. The last year was a good one–so many terrific things happened: our boy turned four, which is a delightful age; the disease remained stable, which is always a source of worry; my writing year went well, which filled me up in ways I find hard to express (ironic, isn’t it–a writer struggling with self-expression?); and my job remained both in-tact and fulfilling.

Oh, so late. It is now two weeks passed the first of the new year, and I have not written down a single revolution for 2015. Maybe it’s for the best. To not have a Revolution in mind for the year. Still, I need organization, but I think a better phrase might be that I need simplification, simplicity, even, in 2015. The last year was a good one–so many terrific things happened: our boy turned four, which is a delightful age; the disease remained stable, which is always a source of worry; my writing year went well, which filled me up in ways I find hard to express (ironic, isn’t it–a writer struggling with self-expression?); and my job remained both in-tact and fulfilling.