So, after much thought, I’ve decided that I’m going to read 13 books by Canadian women this year. I’m calling it “for the ladies.” I’ve got 10 books at home on my shelves just waiting to be read and have chosen three more that I’d like to tackle all before this time next year. In no particular order, the books for my Canadian Book Challenge 2008 are:

Category: trh books

The Canadian Book Challenge (#42, #43, #44)

You’ll just have to take my word for it that I finished on time (4 PM on June 30th) for this year’s Canadian Book Challenge. I had one province (New Brunswick) and one territory (Nunavut) left and was pleased with exactly one of the two. Here we go:

#42 – The Lost Highway – David Adams Richards

I don’t know why I do it to myself. Keep reading Adams Richards, that is. I know he’s a lauded Canadian author who’s won piles of prizes and even more acclaim, but his work is just not for me. This book was beyond hard to get through and I wouldn’t have finished it had it not been for the challenge. The repetition contained within his writing style makes me crazy. It’s as if he finds two or three key elements to each character and continually reminds the reader of them over and over again as the novel progresses. One part murder-mystery, one part typical East Coast depressing drama, and two parts nothingness jammed in to fill up the pages, The Lost Highway is about a warring rural New Brunswick family (there’s a shock) living in a town that pretty much runs the length of, you got it, a road.

The patriarch, a misery of an old man named Jim Chapman, metes out punishment to all around him, including his bumbling, quasi-lost nephew, Alex. A former student of philosophy who can’t seem to do anything right, Alex gravitates from hating his uncle to loving his uncle, from brash irresponsibility to regret, from whimsical romance to stalker, from bumbling fool to calculating criminal throughout the novel. And every five minutes, we get a lecture on what it means to be ethical from the “narrator” who makes a confusing appearance at the end of the novel. I found the setup to be preposterous, the writing tedious, and the story unbelievable. I was captivated for about fifty pages somewhere in the middle of the book where the action heats up, but for the rest of the time I plodded my way to the end trying to find any spare moment so I could just get through the damn book. I know I like to find good things in every book I read, and I just need to remind myself that it’s not that Adams Richards isn’t a good writer, it’s just that his books are for another kind of audience (that doesn’t include the likes of me).

Alas, but all pages do lead somewhere and so I cross New Brunswick off the list.

#43 – Unsettled – Zachariah Wells

Wells’s undeniably charismatic and utterly engrossing book of poetry, unlike the above, held me tightly all through my reading of it. I spent most of Monday with my nephew, a gregarious, spirited little guy who kept me on my toes all day (and who refused to nap). And even though I was tired, I sat down and read the entire book in one sitting, and then went back and re-read a lot of the poems a second time because I liked the titles so much. Having never been to the North, I think the part of his poetry I enjoyed the most is the clash between how you imagine the landscape to be and the writer’s human interaction within it. I also enjoyed the “freight” poems and could definitely see the Milton Acorn comp from the book’s back blurbs. His talent feels raw but the words are obviously chosen very carefully, and that’s my favourite kind of poetry, pieces that feel tossed off by the tips of ingenious fingers that read so easily but you know there were most likely draft upon draft before the author came to the final incarnation. All in all I can’t say enough how powerful I felt the poems to be and if I hadn’t left my copy at home I’d put in some quotes (to be added later).

Huge props to Kate S. for suggesting it and super kudos to Insomniac for sending it priority post so I could take care of Nunavut by the Canada Day deadline.

So that’s it for this year! Now I have to do some thinking about next year’s challenge, which is technically now this year’s challenge because it’s July 3rd today. So. Yeah. Thirteen more Canadian books by this time next year. What to do, what to do.

I do think I’m going to count Night Runner as my first (it’s a YA novel we’re publishing this fall that I read on Canada Day eve and Canada Day after finishing Unsettled) because it’s a book I just adored from start to finish (#44). Anyway. An entire list tk.

#41 – Chasing Harry Winston

My reading table has been heavy with chicklit these days because I’m working on a new project with Scarbie. And for reasons that probably have to do with too much bottled plane air and consistent movement, my concentration has been nil. Enter Chasing Harry Winston. The perfect book to read on the subway into work because you’re too lazy to pump up your bike tires. The perfect book to read before bed because you don’t really miss that much by only getting through 2.5 pages before falling utterly asleep. The perfect book to read without concentration, well, because it doesn’t need any.

My reading table has been heavy with chicklit these days because I’m working on a new project with Scarbie. And for reasons that probably have to do with too much bottled plane air and consistent movement, my concentration has been nil. Enter Chasing Harry Winston. The perfect book to read on the subway into work because you’re too lazy to pump up your bike tires. The perfect book to read before bed because you don’t really miss that much by only getting through 2.5 pages before falling utterly asleep. The perfect book to read without concentration, well, because it doesn’t need any.

Lauren Weisberger has achieved a level of lit stardom few writers achieve. It’s funny, that the US lit stars are all men writing serious fiction, the Jonathons, the Eggers, and the ladies who sell those kinds of numbers are all either British, Irish or Lauren Weisberger writing bland books of a certain genre that will probably never end up on the 1001 Books list. In the end, though, if someone enjoys the book, does any of that stuff even matter? I’ll read anything by anyone, the popular stuff, chicklit, literary fiction, commercial fiction, because all that really matters to me is a good story. And right now, I’m really wondering if chicklit writers can come up with something original. To wit it seems that the purpose of books like Chasing Harry Winston is to make a movie about them two or three years after they’re published. In a sense, couldn’t they save the trees and just skip right to the cinematic version and save us all the trouble?

That said, Weisberger’s latest novel attempts to pull itself up and out of the cliches of its cover (a furry spiked heel with three gorgeous rings stacked from tip to mid-inch). Considering the title is more Plum Sykes than what the actual book is about, and the characters more Sex and the City than anything else, it’s an interesting bit of shoe not entirely fitting the foot, I’d say. Three characters, Emmy, Adriana and Leigh, navigate the final year of their thirties while living and working in New York. Only one of them, Emmy, is truly chasing the married with children dream; the other two look a little deeper in terms of self-satisfaction, Leigh in the form of where she’d like her career to go and Adriana simply needs to grow up. Bits and pieces of the story are told from each girl’s perspective and the characters are well-drawn, quite engaging and utterly trapped by their circumstances at the moment. Weisberger plays the role well, they wear “the latest” Chloe shoes, are cognizant of trends and fashion, but you can feel her writing trying to pull away from the cliches as she attempts to be a little less “chick” and a bit more “lit.”

There are conflicts, petty jealousies, and the reader wishes again and again for the book to delve a bit deeper into the idea of female friendship and less into silly “pacts” and false start-ups to plot. In the end, I can’t say that I didn’t enjoy the book, because I did, and I can’t say that Weisberger isn’t a talented writer, because she obviously is, I just hope that her next book abandons all pretense of Harry Winston and lets her spread her wings a little.

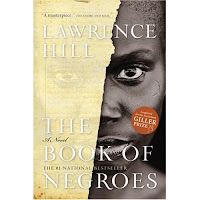

#40 – The Book Of Negroes

There are few books these days that can honestly be called epic. Many that aspire to be so, and many writers who set out to be “epic” without really understanding that it’s not just page count that matters when a book stands up and marks its place in time. Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes is epic and it surely marks its place in time.

There are few books these days that can honestly be called epic. Many that aspire to be so, and many writers who set out to be “epic” without really understanding that it’s not just page count that matters when a book stands up and marks its place in time. Lawrence Hill’s The Book of Negroes is epic and it surely marks its place in time.

Over the past weekend when we were in NYC with my RRHB’s parents, he was the Author of the Year at the Libris Awards. That says a lot, it’s an award decided upon by booksellers and not a jury. Last year, Ami McKay won for her haunting, beautiful, and uplifting The Birth House. The books that win please readers and booksellers alike, a little bit commercial, a lot literary, and with a story that seems endless in its scope and telling, I’m not surprised at all that The Book of Negroes, and Lawrence Hill, won this year.

The novel finds Aminata Diallo, a young African girl aged about eleven, growing up as many generations before her have grown up. She has a mother, a father, a religion (she’s Muslim), a village, and is in training to follow her mother into midwifery. But everything changes the moment she’s captured by traders and sold into slavery. Transported by ship to the southern colonies before they’ve become the United States, she barely survives the journey. After she arrives, she’s branded, sold, and taken under the wing of a woman who ensures she comes back to health. And the story simply doesn’t stop there, she’s sold to a Jewish man who treats her well, but keeps her enslaved.

More skilled than many, especially other women, Meena, as she’s known, can write and read. Skills that serve her well and help her to survive the many injustices life tosses her way as easily as paper carries on the wind. The second half of Meena’s life finds her freed, a member of the new loyalist colony in Nova Scotia. Still unhappy at the crown’s treatment, a group of Nova Scotians travel back to the motherland and settle in Freetown, on the coast of Sierra Leone.

I read this book to satisfy my Nova Scotia requirement of the Canadian Book Challenge. I had planned on reading a Lynn Coady novel, but once this novel won the Commonwealth Prize, I figured I should probably read it sooner rather than later. And wow, what an achievement for Hill, it’s a wonderful and important book. The sadness of Aminata’s story is tempered by her own words, her strength and her amazing sense of herself in the world. Despite the hardship, despite her children being taken away from her at different stages in the book, despite being bought and sold and then bought again, despite the aches in her bones, she tells her stories again and again, all in aid of ending the terrifying and awful trade in humans.

Honestly, I enjoyed every moment of this book, even if it did take me three weeks to read. Now, I’ve got two provinces/territories to go before July 1st and only one slight problem. Anyone have an idea about reading Nunavut?

#39 – The Importance Of Being Married

First, a confession. I adore Gemma Townley. Personally, I think she’s one of the best writers working in chicklit these days. Her characters are never cliched beyond repair, her stories are always original while remaining within the bounds of the genre, and even if the girl always get the boy at the end (even if it’s not the boy she thought she’d end up with), how she gets there is consistently original and charming.

First, a confession. I adore Gemma Townley. Personally, I think she’s one of the best writers working in chicklit these days. Her characters are never cliched beyond repair, her stories are always original while remaining within the bounds of the genre, and even if the girl always get the boy at the end (even if it’s not the boy she thought she’d end up with), how she gets there is consistently original and charming.

Jess, the main character in Townley’s latest novel, The Importance of Being Married, doesn’t believe in marriage. But when a combination of pure goodness and luck leaves her with an inheritance neither expected nor necessarily appreciated (at least at that moment in time) considering it comes with a caveat. The lawyer handing over the property thinks she married. And why does he think Jess is married? Because she told the kindly old lady she’d be visiting in the home a very long, detailed story about how she married her gorgeous, successful and utterly charming boss. Oops.

So, Jess and her roommate quickly sum up a plan called operation marriage or something of the like, as if it’s a project to be managed, and work on getting her married by the time the two-week deadline to inherit arrives. Hilarity ensues. As does a little old-fashioned honesty. It’s a happy ending. I’m sure that’s not a spoiler, it’s chicklit after all, and I’d be curious to see what Townley would come up with if she wasn’t sticking to a rigorous book-a-year publishing schedule and stepped outside the genre just a little. I’m sure we’d all be pleasantly surprised.

IMPAC Win

Quinn posted up a note this morning that Rawi Hage has won the IMPAC award. I only made it through three of the shortlisted books (too many challenges; too much travelling; very little reading) but DeNiro’s Game was one that I read and loved. It’s nice to see novels that were shortlisted for Canadian prizes, like the book I’m currently about 20 pages away from finishing, The Book of Negroes (which just won The Commonwealth Prize), go on to win international prizes. It’s not as if I’m writing a “here’s the trouble with the Giller” note or anything, but I’m glad that both DeNiro’s Game and The Book of Negroes will go on to find larger audiences as a result of the attention.

Posting has been sparse, life seems to be overwhelmingly busy these days. And we’re on the road again tomorrow, taking a family trip to NYC. Right now I feel like I’ve been travelling for months. And for those moments where I’m sitting behind my desk staring out the window thinking how nice it would be to have a job where I travelled even more, I’ll need to remember this feeling. The one where I just want to be home with a good book, my two working hands, and some time to get caught up on my writing.

#38 – Gilead

Over the course of the 10 days I was away, I stopped and started a number of books. But Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead was the only one out of the five or so paperbacks I brought with me to capture my exhausted attention and hold it tight in its hands.

Over the course of the 10 days I was away, I stopped and started a number of books. But Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead was the only one out of the five or so paperbacks I brought with me to capture my exhausted attention and hold it tight in its hands.

The narrator, a Reverend John Ames, nears the end of his life and wants to leave a record behind for his only son, a seven-year-old boy. Told in epistolary format, the Reverend mixes scripture, sermons, stories and observations into the narrative of his life, loves words and their meanings, and takes the spirit of his life very seriously. He means to leave a legacy behind for his son; it’s the only way, he’ll not survive into his adulthood. Interwoven into his own history is that of his grandfather, his father (both reverends as well) and his neighbour, an aging Presbyterian minister, Boughton.

Novels that are technically brilliant, novels like this one, make one appreciate the sheer talent that a voice can bring to a book. Ames’s remains loud, clear and unclouded throughout the entire novel. Robinson uses the form to her advantage, and you can hear the tenor reverberating throughout each sentence of the love letter to his son. There were so many passages that I wanted to soak up like clouds do mist and the book is so heartfelt that one can’t help but feel that Marilynne Robinson’s Pulitzer was utterly and rightly deserved.

Here’s a passage that I put up earlier this week on Savvy Reader:

Our dream of life will end as dreams do end, abruptly and completely, when the sun rises, when the light comes. And we will think, All that fear and all that grief were about nothing. But that cannot be true. I can’t believe we will forget our sorrows altogether. Sorrow seems to me to be a great part of the substance of human life.

Just, astonishing and awesome, as in its original meaning. Truly.

PHOTO IN CONTEXT: I read the bulk of this book in the Jardin des Tulieries in Paris after visiting the Musee D’Orsay after Sam went home on Friday. Also included is me in thoughtful repose, flaws, freckles, dirty hair and all.

PHOTO IN CONTEXT: I read the bulk of this book in the Jardin des Tulieries in Paris after visiting the Musee D’Orsay after Sam went home on Friday. Also included is me in thoughtful repose, flaws, freckles, dirty hair and all.

#37 – High Crimes

If anyone’s familiar with my reading habits, you know that I don’t read a lot of nonfiction. But it seems the nonfiction that always grabs my interest are nightmare stories about Mount Everest. I read Into Thin Air in about 20 minutes, and my curiosity of the people who willingly put themselves through the grueling, punishing task on purpose always gets the best of me. I only wish my interview with Peter Hillary was still live on the National Geographic Canada web site so I could link to it — we talked for two hours and it was, to date, the best interview I have ever done.

If anyone’s familiar with my reading habits, you know that I don’t read a lot of nonfiction. But it seems the nonfiction that always grabs my interest are nightmare stories about Mount Everest. I read Into Thin Air in about 20 minutes, and my curiosity of the people who willingly put themselves through the grueling, punishing task on purpose always gets the best of me. I only wish my interview with Peter Hillary was still live on the National Geographic Canada web site so I could link to it — we talked for two hours and it was, to date, the best interview I have ever done.

Annnywaaay. High Crimes: The Fate of Everest in an Age of Greed. Michael Kodas’s book has a point to prove, and it’s quite compelling: How is it that crimes that take place at 8,000 metres are not considered so, when they’d be heavily punished back at sea level? Unskilled guides passing themselves off as “experts” leading unsuspecting tourists up a mountain to perish is doing damage to the very serious sport of mountaineering. It’s ruining Everest. As is greed, human selfishness and the age-old challenge of tackling all of the biggest peaks in the world. His tale centres on two specific stories: the crumbling of his own expedition from ego, theft and a whole host of other problems; and the death of a doctor, left behind by a man who had a reputation for being not only a liar but one utterly unqualified to be a guide.

How can you just leave someone behind when he’s your responsibility in the first place? When does summiting become so all-consuming (for its material benefits) when it costs the life of someone who trusted you to take them up and then back down? It’s an impossible question. It’s easy to know your own moral code, your values, until you’re thousands of metres in the air, deprived of oxygen and the weather turns. But there’s a difference between malicious intent and an accident, the feeling of getting yourself in over your head. Even experienced climbers get into trouble, but that’s the point that Kodas, and many writers like him consistently make, Everest has become so commercial that people think they can just buy their way to the top.

On more than one page, I was utterly horrified by what I’d just read. Greed, mayhem, even murder in a place where people are supposed to be in awe of the sheer power of the Earth itself. And even while Kodas’s writing tends to the sensational (it’s very headliney, if that makes any sense), it’s an easy book to read. Perfect for a plane ride to Paris, I’d say.

PHOTO IN CONTEXT: The ARC I got from work on my tiny plane tray.

Oh Gawker, Yawn

Loving to hate remains one of the most entertaining reasons for reading Gawker. But sometimes, sometimes you need to roll your eyes. They’ve had a hate-on for James Frey ever since the story broke, which means that this latest barrage of “investigative” journalism around his novel should come as no surprise. But my only question is when should people just start burying the hatchet and letting it all go? There’s a disclaimer at the beginning of the book that reads simply: “Nothing in this book should be considered accurate or reliable.” So I know it’s an easy potshot to take then, muddling about in what I’d consider to be the lesser aspects of the novel, the multiple lists and “fun facts.”

Although the Gawker piece is tongue-in-cheek, it must get tiring to be writing and reporting the same old story again and again. But in the same sense, you’d think Frey would learn the lesson, and maybe double check whether or not actual facts are correct. In the end, though, I guess it’ll continue to be an easy criticism to make and to level against him, regardless of how many books he manages to sell in his lifetime.

#36 – The Secret History

Donna Tartt’s epic The Secret History feels at times over-wrought, over-written and perhaps many, many pages too long. That said, holy crap did this novel grab me by the toes and pull me in from beginning to end. To summarize: it’s the story of a young, unhappy man from Plano, California who finds himself embroiled in a murderous plot at an exclusive college (called Hampden) in Vermont. But the book is also so much more than that — it’s the dramatic coming of age for a young man who searches for something exciting and finds himself deeply embroiled in events that will change his life forever.

Donna Tartt’s epic The Secret History feels at times over-wrought, over-written and perhaps many, many pages too long. That said, holy crap did this novel grab me by the toes and pull me in from beginning to end. To summarize: it’s the story of a young, unhappy man from Plano, California who finds himself embroiled in a murderous plot at an exclusive college (called Hampden) in Vermont. But the book is also so much more than that — it’s the dramatic coming of age for a young man who searches for something exciting and finds himself deeply embroiled in events that will change his life forever.

The narrator, Richard Papen, has had an ugly childhood: his parents are typically unhappy, he’s poor, an only child, and longs for a world far different from the one he grew up within. Enter Hampden College. And even better, enter his acceptance into a small fraternity of students, six including Richard, that study Greek under an epic teacher named Julian Morrow.

The group’s leader, Henry, a wickedly smart (he speaks six languages or something crazy like that), embarrassingly rich fellow who controls the group. Besides Richard and Henry, there’s Charles and Camilla (twins), Francis, and Bunny (real name Edmund). All five were reared at prep or private school, and all five both accept and reject Richard at the same time. The secret history of the novel’s title revolves around the events that fall out of a weekend where the core five, Richard excluded, attempt to create a true bacchanal in the woods around Francis’s property. It’s impossible for any of them to move forward beyond the events that happened over those few days and the book meditates on those moments in your life that impact where you’ll end up, the idea of a ruinous youth, and the consequences to thoughtless actions.

Tartt unravels the novel like a mystery with masterful suspense. Richard slowly goes through the motions of telling the story, which has become ‘the only one he’ll ever be able to tell,’ to the reader and in part finally letting the history consume him once again if only to finally let it all go. Elements of Highsmith and other solid British writers (Tartt’s an American) sneak into her prose and characterization (Henry is a solid Ripley-esque fellow, right down to his glasses), and I found the most frustrating part of the narrative never knowing exactly when the novel is set. But in the end, it’s a terrific book that sucks you right in and would be perfect for summer reading up at the cottage when it’s cold (like today) and raining (like today) and all you’re looking to do is curl up by the fire with a good, hair-raising story.

READING CHALLENGES: Believe it or not, The Secret History is on the 1001 Books list, and so it was on my particular challenge list for this year. I think I might be slightly behind the whole 1001 Books challenge for now, having given up Huck for the present time.

WHAT’S UP NEXT: Saints of Big Harbour, a nonfiction book that I started while waiting for the osteopath this afternoon called High Crimes, and whatever I’m going to take to Paris (probably the two IMPAC books I actually have and anything else that’ll fit in my suitcase and, of course, a Jane Austen because I always love to read her on a plane).