Sometimes I really resent the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die list. Like when you slog through umpteen pages of books like Philip Roth’s bloated and self-indulgent masterpiece American Pastoral. I’m honestly shocked that a book that so clearly needed an editor won the Pulitzer Prize. I liken Roth’s writing in ways to Canadian David Adams Richards, who remains highly regarded by many people in the literary world (and is ever-acclaimed and never-endingly nominated). It’s just not the book for me. Honestly, I’m barely surprised that I finished.

Sometimes I really resent the 1001 Books to Read Before You Die list. Like when you slog through umpteen pages of books like Philip Roth’s bloated and self-indulgent masterpiece American Pastoral. I’m honestly shocked that a book that so clearly needed an editor won the Pulitzer Prize. I liken Roth’s writing in ways to Canadian David Adams Richards, who remains highly regarded by many people in the literary world (and is ever-acclaimed and never-endingly nominated). It’s just not the book for me. Honestly, I’m barely surprised that I finished.

In theory, and at the beginning of my reading experience, I couldn’t put the book down. I was fascinated by Seymour “The Swede” Levov, the golden-blond, all-American, football-playing, Riggins-reminding main character. The novel does an excellent job of exploring how his Jewish roots somewhat sit in opposition to his golden boy lifestyle thus setting up this ideal of the American pastoral. In a world where a man, who has worked incredibly hard (he took over his father’s glove business) and married a woman he adores (and is a beautiful Irish-American beauty queen), can’t even succeed, what hope is there for the rest of us? The Swede’s more than a character: he’s an archetype, one that Roth’s narrator, the bachelor-slash-writer Nathan “Skip” Zuckerman explores in tireless detail.

After a chance meeting at a baseball game when they’re both well advanced into middle age, The Swede approaches Skip and asks if he’d like to write a book about his father, Lou Levov. This becomes the premise behind telling the Swede’s story. And then retelling it. And then retelling it a little more. And then a little more. Like a record that skips, the book plods along in ceaseless and sometimes utterly unnecessary detail about every aspect of the Swede’s life, his relationship with his first wife, Dawn, and their troublesome daughter, Merry.

When Merry’s (as described on the jacket) “savage act of political terrorism” destroys the family, much of the novel is dedicated to trying to understand the reasons behind why she did it. The breakdown of the family is never explored in detail, only hinted at, as we discover at the beginning of the book that the Swede has remarried and has three teenage sons. For the majority of the novel, he tries to keep his life on course despite it’s consistent derailing. As the nature of tragedy in and of itself is cyclical, I can see why Roth spent so much time writing around and around the events; but it took a sheer force of will for me to finish this book.

I am not, however, giving up. Anyone who can write sentences like Roth deserves a second chance:

Marcia was all talk — always had been: senseless, ostentatious talk, words with the sole purpose of scandalously exhibiting themselves, uncompromising, quarrelsome words expressing little more than Marcia’s intellectual vanity and her odd belief that all her posturing added up to an independent mind.

I started The Plot Against America this morning and am already enjoying it. Also, let’s make note that I read the majority of this book during my own tedious and utterly frustrating moments: waiting for the doctor; waiting for the ferry; riding on the ferry; sitting in the car and waiting for the ferry…and so on. Maybe that had something to do with my frustration?

I started The Plot Against America this morning and am already enjoying it. Also, let’s make note that I read the majority of this book during my own tedious and utterly frustrating moments: waiting for the doctor; waiting for the ferry; riding on the ferry; sitting in the car and waiting for the ferry…and so on. Maybe that had something to do with my frustration?

READING CHALLENGES: Yes! A title in my woefully underrepresented 1001 Books Challenge and if I were actually still doing the Around the World in 52 Books I might have counted this title for the United States.

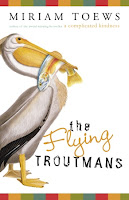

PHOTO IN CONTEXT: The book. My lap. The ferry. Boredom.