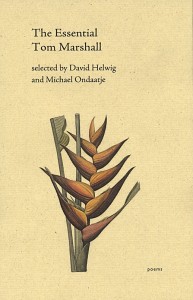

The latest in Porcupine Quill’s ongoing series, The Essential Tom Marshall, co-edited by David Helwig and Michael Ondaatje, seeks to preserve and celebrate the work of the Kingston poet in a tidy, eclectic volume of work. Let me make a confession: I have two degrees in English and have studied Canadian writing for years. I work in publishing. I have (years ago) published some poetry of my own and, yet, throughout the travels of my literary life I have never come across Tom Marshall — I even went to school in Kingston, lived there for many years, and am ashamed to say that I had never heard of him before the package arrived on my doorstep from the publisher.

The latest in Porcupine Quill’s ongoing series, The Essential Tom Marshall, co-edited by David Helwig and Michael Ondaatje, seeks to preserve and celebrate the work of the Kingston poet in a tidy, eclectic volume of work. Let me make a confession: I have two degrees in English and have studied Canadian writing for years. I work in publishing. I have (years ago) published some poetry of my own and, yet, throughout the travels of my literary life I have never come across Tom Marshall — I even went to school in Kingston, lived there for many years, and am ashamed to say that I had never heard of him before the package arrived on my doorstep from the publisher.

And it’s a shame because I adored these poems. As someone who slogged through winters at Queen’s, I can honestly say that there was no mysticism left in me when I finished my undergraduate degree, and yet, the ability for Marshall, in the opening poem entitled ‘The park is more like a wood,’ to bring his sensibility to an every-day park seen from a bedroom window. In a sense, this first piece uses traditional symbolism, calling back, in a way to the Romantics who did the same–heightened nature in verse with an eye to discussing human nature–especially towards the beginning of the poem where the ‘moon bends, beckoning our lips and bodies back,’ and irresistible pull. And yet, he refuses to leave it there, choosing instead to invert the symbolism in a sense, an utterly modern worldview where: “Sun blooms in our bodies / like a soft death / a warmth that is far more permanent than love.” And his park is inhabited, later, in “Fall” by “perverts of several kinds,” one must love “through” as “the bruise of life burns outward.” It’s a glorious poem, as the narrator stands both aside and within the part at various points during the year, observing life from within but knowing you must live through it, and necessarily knowing there’s a varying difference between watching and seeing.

The parks, the places, the pictures in these poems are ever-moving from heightened symbolism and back to stark realism. The poet who believes the park eternal (in “Coda: Macdonald Park) realizes that “leaf and lost desire” curves, ever-shifting, nature a part of him as we became aware in the previous poem (“Interior Monologue #666) where becoming a “slow, lethargic vegetable” (a rutabega) becomes further proof of the inability, of this narrator, to distinctively separate himself from the natural world.

It’s always hard to write about poetry because it contains such a personal experience with language. So different from the novel, where you get lost in a character, pulled out of yourself, deceptively simple works like these do the exact opposite–the simple choice of words serve to highlight your own relationships, your own experiences in a park, your own utter inability to love properly, perhaps even greatly. As Marshall says in “Strictly Personal”: “If I could / always have been so / open how different / things might have been.” In a sense, as the leafs fall off the trees, decay and melt back into the ground in so many of these works, the poet too looks back upon a life that’s melted away–where choice would have been different had he/she lived “by the dream / however strange…”

The Essential Tom Marshall does its job incredibly well, celebrating a poetic gift that’s both light and intense at the same time–the simple structure and relatively easy language open up the depth and resonance of this work almost immediately. I read the book through twice in two days and would happily again and again, I’ve ear-marked at least a half-dozen poems, and let them echo through me. I was inspired and aching on the subway in the last couple days just to be able to write a little bit on my own–truly, that’s the gift of a great poet, is it not?