I’ve been wanting to write more about pop culture lately with a cute new title: “Mom and Pop (Culture).” However, therein lies a bit of a problem… I’m really not devouring the same amount of pop culture as I once did, and when I get around to it, the whole fad has passed or I’m simply too old to get it, like One Direction (I mean, we watched them on SNL and it was highly, um, entertaining?). Then I thought I could write a whole blog post about how funny I find Up All Night, especially Maya Rudolph, and when Christina Applegate made the crack about almost fitting back into her pants both standing up AND sitting down, I’m peed a little it was so funny. And we haven’t really been watching that many movies, for obvious reasons. My in-between-book reading consists of Today’s Parent, Chatelaine, The New Yorker, Oprah (sue me; it’s a great magazine), and Best Health, all of which are truly just a conduit for free recipes. Not very hip. I stopped my subs to Toronto Life and House and Home, among others, because the piles of magazines were unwieldy. Again, not so hip. Then again, I read Wired on my iPad. That’s kind of hip, right? I read piles but not so much the trendy books, there are no shades of grey currently on any of my devices. So… what to talk about?

I’ve been wanting to write more about pop culture lately with a cute new title: “Mom and Pop (Culture).” However, therein lies a bit of a problem… I’m really not devouring the same amount of pop culture as I once did, and when I get around to it, the whole fad has passed or I’m simply too old to get it, like One Direction (I mean, we watched them on SNL and it was highly, um, entertaining?). Then I thought I could write a whole blog post about how funny I find Up All Night, especially Maya Rudolph, and when Christina Applegate made the crack about almost fitting back into her pants both standing up AND sitting down, I’m peed a little it was so funny. And we haven’t really been watching that many movies, for obvious reasons. My in-between-book reading consists of Today’s Parent, Chatelaine, The New Yorker, Oprah (sue me; it’s a great magazine), and Best Health, all of which are truly just a conduit for free recipes. Not very hip. I stopped my subs to Toronto Life and House and Home, among others, because the piles of magazines were unwieldy. Again, not so hip. Then again, I read Wired on my iPad. That’s kind of hip, right? I read piles but not so much the trendy books, there are no shades of grey currently on any of my devices. So… what to talk about?

Let me backtrack. When I was a teenager, I found a copy of Exodus among my parents records. I took it upstairs and listened to it, a lot. It was my mother’s. My dad didn’t even know it was there. At the time, I was 15 and working at Baskin-Robbins with a delightful woman named Yvonne Chin, she was Jamaican. I asked her if she knew who Bob Marley was (yes, I was the dopiest kid, like, ever). She came in the next day with a stack of records almost as tall as me and I listened to all of them. Taped them, bought my own copies, bought more tapes and CDs, and then before I went to university my brother bought me the Songs of Freedom box-set for my birthday and I have not stopped listening to it since. I was obsessed. I read Jamaican writers (Michelle Cliff remains a favourite), I wrote papers and integrated Bob Marley lyrics into them. I listed to “Pimper’s Paradise” about 8,753 times in my old Nissan as I drove around during my first few years of university. I stayed up way too late in high school one night watching the only concert footage I had ever seen of Bob Marley on the CBC. I even went so far as investigating grad school at one of their universities (the cost was prohibitive, completely). I know I’m not the only one. There are millions like me.

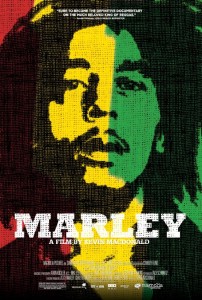

Kevin MacDonald’s documentary is excellent. It’s thoughtful, provocative, and barely uses “Redemption Song” (except in a really rough mix, which I appreciated). Seeing the evolution of reggae and how Bob Marley’s music influenced, not only generations, but entire countries, had me choked up on more than on occasi0n. That he fought for the liberation of Zimbabwe only to have it all come crumbling down is heartbreaking. His politics have become all but forgotten, in a sense, when his music is played on easy listening stations to signifying the start of summer patio station. But the film does more than follow the evolution of Bob Marley from young musician to superstar — it looks closely at how he became “Bob Marley,” the icon, and breaks it all back down so the world can see Bob Marley, the man. The most striking part of the documentary for me was a rare clip from an interview where they were discussing the assassination attempt. When asked if he would still perform, Marley answered: “What is was meant to be.” Not performing wouldn’t stop someone from shooting him if that was the intention. Marley, the man, was in the world, the music was there, the unifier, pulling the hands together of Manley and his opposition, he stood on stage and it was important. It was real. It was revolutionary.

And now, it’s different. Sure, the whole world knows “Redemption Song,” and so they should, it’s a beautiful piece of music, but has the magic disappeared? Has its cultural significance evaporated by muzak and terribly dirty teenagers who grow dreds without truly understanding the Rastafarian ways? Does any of that matter? Is what’s important how epic Bob Marley has become — like Che Guevara — where his likeness is as familiar to us as our own, can we celebrate the shift to icon and be okay not knowing how instrumental he was both politically and musically? That’s the amazing balance that MacDonald’s documentary strikes: it’s an impressive, beautiful, wise, and compelling work that does both, proves Marley worthy of his iconic status while humanizing him at the same time. I’m still thinking about it so deeply, which is always the sign of a good documentary, right?