When I was a teenager, I visited Russia for a school trip. It was March break so it was cold, snowy, winter. We spent an afternoon in the Hermitage Museum, founded by Catherine the Great in 1764. It was magnificent. It fostered a love of art and museums in me that continues to this day. I don’t consider it travelling unless I’ve visited an artful place.

When I was a teenager, I visited Russia for a school trip. It was March break so it was cold, snowy, winter. We spent an afternoon in the Hermitage Museum, founded by Catherine the Great in 1764. It was magnificent. It fostered a love of art and museums in me that continues to this day. I don’t consider it travelling unless I’ve visited an artful place.

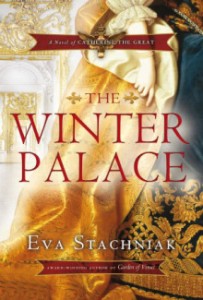

I have fond memories of Russia, and so I knew the setting alone would endear Eva Stachniuk’s novel to me, even before I started. Sometimes, a book is simply as good as its storytelling: frank, honest, compelling, and that’s exactly the case with The Winter Palace. The book opens with a confession, its narrator, Barbara (“Varvara”), is a “tongue,” a spy in the Russian court. First, she works for the Empress, Elizabeth, and then for the Grand Duchess of all the Russias, Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst, who later becomes Catherine the Great.

There’s court intrigue, arranged marriages, love affairs, friendship, betrayal, birth, death and everything in between, and Varvara sees it all. She trusts perhaps where she shouldn’t, and lies where she needs to — everything to keep her place, and that of her family, safe. Loyalty is traditionally unheard of, or it’s unbearably stifling for those not destined for the throne, and Varvara learns this lesson the hard way as the old reign makes way for the new.

In a sense, politics drives every part of this novel: gender politics as it defines the roles between men and women, royal or not; the state of the union as legions fail and weakness becomes apparent; the fight for position in terms of the court; and how to feel useful when one is the lowest rung on the ladder, as Varvara starts her life in the Palace.

Like any interesting character, Varvara evolves because she’s smart and knows how to assess a situation and act quickly, accordingly. She works hard, even if it means plotting, if it means spying, because she has no other choice. Rewards are bittersweet, and even confusing at times, especially when your choices are limited. But what Stachniuk shows so well is that even the men are weakened by their own positions, their own greed and misunderstandings in the face of the ever-corrupting lure of power.

Varvara intertwines her fate to that of Sophie’s. They become friends. Their presence in each other’s lives a welcome bit of happiness. Varvara means well, but in the end, it’s power that betrays her, or, rather, what that power betrays in and of itself, if that makes any sense. The book hums along, and I was tweeting about this earlier in the month, one night small letters and hidden spaces invaded my dreams. Another weekend I was bereft because I had forgotten the book at work — these are all good signs. Signs that this book gets under your skin in exactly the right way, keeps you up at night when you should be sleeping, and almost makes you wish you were there (or at least seeing a big screen version complete with really good casting). The Winter Palace kept me up well passed my bedtime when I finally got it back. I was okay with that.