Way back in the way back, when I started working in publishing as a lowly little Digital Marketing Manager at Random House of Canada, I had the pleasure of working with Ami McKay, whose first novel, The Birth House, charmed even the most cynical among us lowly bibliophiles (read: me). For years afterwards, I sent many authors towards Ami’s website, Twitter feed, etc., as a picture perfect example of how to build a really terrific digital footprint. McKay is open, honest, forthright and utterly authentic — it’s impossible not to like her. You know?

Way back in the way back, when I started working in publishing as a lowly little Digital Marketing Manager at Random House of Canada, I had the pleasure of working with Ami McKay, whose first novel, The Birth House, charmed even the most cynical among us lowly bibliophiles (read: me). For years afterwards, I sent many authors towards Ami’s website, Twitter feed, etc., as a picture perfect example of how to build a really terrific digital footprint. McKay is open, honest, forthright and utterly authentic — it’s impossible not to like her. You know?

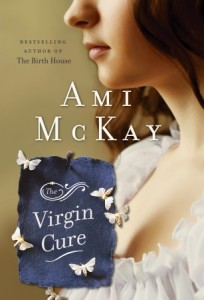

So I kept all of this in mind when I was reading The Virgin Cure. It becomes harder and harder to read books, and then review them critically and/or comprehensively read them without allowing for personal feelings to creep into my thoughts about the book. Reading Ami McKay’s blog, you know immediately how much research she had done for the novel; you understand the personal connection to the topic; and you feel her very intense dedication to her work. It’s lovely that it’s utterly apparent that all of this is totally apparent in the end result as well.

Moth, part gypsy, part lost girl, lives with her fortune telling mother in a tenement building in New York’s Lower East Side. When her mother sells her off into the service of a wealthy woman, Moth takes her future in her own hands. The opportunities for young girls, orphaned, abandoned, are not great and, yet, Moth does what she has to in order to survive. McKay’s novel is heavy on action — it rips along like some of the best historical thrillers I’ve read, reminding me of books like Slammerkin and Fingersmith. While there’s no overt “twist” like there is in either of those novels, there is a somewhat shocking reveal that I won’t go into too much detail here so as not to spoil it.

Moth makes her way but at what cost? McKay attempts to address ‘how the other half lives’ by framing Moth’s story with the life and experiences of her ancestor, a female doctor, who took care of the working women of the Lower East Side (the novel’s title refers to an apparent “cure” for syphilis, which was sleeping with virgins). In the novel, Dr. Sadie, who feels like an urban Dr. Quinn Medicine Woman (which is all in my head — there’s no overt reference, obviously), swoops in and provides care for a class of women who would otherwise be left unseen. Eventually, Moth lands at an upscale brothel filled with young girls who are sold off to the highest bidder for their, ahem, deflowering. And when she tries desperately to control her own ending — the who and the why and the where, it becomes readily apparent that no matter how “nice” the madam, Miss Everett, remains, she has an ulterior motive, and her girls are property, her income is protected and their rights are suspended.

McKay excels at writing utterly readable novels that explore issues of women in history in ways that aren’t staid or stuffy. She knows what makes a good story and sticks to her guns throughout the book. Also, McKay has written a truly fantastic opening sentence, one that’s just about the best that I’ve read in years. I was green with envy when I read it, in a good way. There’s a lot to enjoy with this novel — getting sucked into the story and having it carry you along for one thing. But I was very curious about Dr. Sadie, I wanted to read more of the book from her perspective. I know Moth’s story is solid, but her voice is definitely speaking to a well-trod tradition; Dr. Sadie’s, not so much. Regardless, the spirit and essence of this novel kept me reading well passed my bedtime, which, for anyone who knows how tired I am, is the greatest compliment I can give any writer these days.

I really enjoyed this book. I must get around to reviewing it! I am glad you liked it, too. 🙂