I have spent three days this week at various doctors appointments and sitting waiting for blood work, and managed to read three books in five days. It’s almost like I’m breastfeeding at all hours again, only I’m not. Actually, it’s nothing like that at all. In fact, it’s exactly the opposite. Regardless, here are some short reviews of books I’ve read lately.

I have spent three days this week at various doctors appointments and sitting waiting for blood work, and managed to read three books in five days. It’s almost like I’m breastfeeding at all hours again, only I’m not. Actually, it’s nothing like that at all. In fact, it’s exactly the opposite. Regardless, here are some short reviews of books I’ve read lately.

#44 – Saturday Night and Sunday Morning by Allan Sillitoe

Sometimes, when you see the filmed version of a book first, it’s almost impossible not to replay the movie in your head as you read. In the case of Allan Sillitoe’s Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, this was entirely the case. Luckily, both the book and the film are excellent, so I wasn’t disappointed by anything happening in my own head as I read. Sillitoe’s portrait of a young man, a working class, philandering, hard-drinking, impulse-driven, anti-hero remains captivating over 50 years since its publication. I found myself violently engrossed in the film, at times disgusted by Arthur Seaton’s behaviour, his attitude towards women, his own selfishness, and yet utterly thrilled by his voice, his hard-driving anger, and his youth.

Set in a working class section of Nottingham (and forgive me if it’s all working class; I am not familiar with the geography), Seaton works at a bicycle factory, where he gets paid by the piece. Work too fast, and you make too much money, the big bosses will come down on you; work too slow and it isn’t worth your while to get up in the morning. There’s a tender balance Seaton strikes between boredom, completely shutting off to the redundancy of his tasks and letting his mind wander (usually to the state of his love life, which is complex, and full of many married ladies). He served in the army but has no faith in it; he drinks not just because it’s the only thing to do but because it IS the thing to do; and all of his relationships with women are based on lying, cheating and his own awkward concepts of love. Yet, as a character, I couldn’t help but adore him — a prototypical bad boy when it still meant something to buck the system, and the dichotomy of the two parts of Seaton’s life: the Saturday nights spent drinking and with his hand up the shirt of his many married lovers; and the Sunday morning when he goes fishing and perhaps decides upon one girl, nicely contrast the tenor of life in England after the war. Everyone needing to find their footing, their voice, after the collective “pulling together” (Keep Calm and Carry On) as a universal decree. All in all, it’s an excellent novel. (Also exciting is that it’s on the 1001 Books list, whee!).

#45 – State of Wonder by Ann Patchett

Ann Patchett is one of my favourite American novelists. I adored Run, enjoyed Bel Canto, and had my heart broken over Truth & Beauty. But State of Wonder is in an entirely different class — if I had to find a comp, like someone (I can’t remember who) mentioned on Twitter, I’d too suggest Barbara Kingsolver’s The Poisonwood Bible. But, truly, the unbridled success of this novel lies in Patchett’s almost post-colonial “talking back” to Joseph Conrad’s classic Heart of Darkness. Now, I read Conrad’s book in first year university and haven’t revisited it since, so it’s hazy, to say the least in my memory. I recall more of Apocalypse Now than I do the novel itself but that doesn’t mean that I can’t theorize that Patchett set out to write back to Heart of Darkness, tackling not necessarily themes of colonialism and “going native” (shuddering to write that sentence) but more so the toll and cost of medical research takes from on our “modern” world.

When Dr. Marina Singh’s workmate and lab partner, Dr. Eckman, is pronounced dead in a far flung letter from Dr. Annick Swenson, a research doctor who has been in the field for almost decades developing and studying a very particular tribe in order to create a fertility drug that could revolutionize women’s reproductive health, she (Dr. Singh) is sent out to retrieve the true story and maybe, just maybe, bring both the body and a report of where the work actually is back to the company for whom they all work. Things go wrong for Marina right from the start — her suitcase is lost, her clothes taken by the Lakashi tribe when she arrives in camp, and soon every vestige of Western life has disappeared from around her. She wears her hair plaited by the Lakashi women, the only dress she has comes from them as well, and without sun protection, the half-Indian Marina’s skin bronzes so deeply that even she notices how different she looks than when at home suffering through a long, terrible Minnesota winter.

Classically trained as a OBGYN, Marina gave up her medical practice due to a terrible accident, and has been a pharmacologist ever since. Yet, once she finds Dr. Swenson (and the path that got her there was no less than difficult), her skills as a doctor are called upon — an in unclean, unhygienic and utterly disorganized (in terms of performing surgeries), and Marina’s life takes a turn in a direction she never imagined. The novel’s ending, both spectacular and breathtaking, has perfect pacing — I couldn’t put it down, and it brought me to my knees. I found myself reading and reading, any chance I could get, morning, deep into the night, just to find out what happens. And the last sentences, just like the amazing ones that end The Poisonwood Bible, stayed with me for days. Highly recommended; it’s perfect summer reading in my humble opinion.

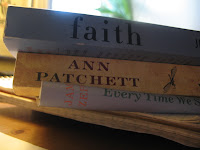

#46 – Faith by Jennifer Haigh

I’m going to be honest — the subject matter of this novel remains difficult for many reasons — the church and its history/current struggle with pedophilia doesn’t necessarily equate “light,” “breezy” read. Yet, the tone and undercurrent of Jennifer Haigh’s novel, while neither light nor breezy, is both generous and kind, a difficult balance to achieve when discussing Catholic priests and the matter of faith in general. The narrator of the story, a self-proclaimed (at the beginning of the novel) modern-day “spinster,” Sheila McGann retells a story her half-brother Art, a priest who has found himself embroiled in a scandal that threatens not only his livelihood but also his life, and his core beliefs.

Sheila returns to Boston to help her family in the time of crisis. Art, accused of an unspeakable act with a young boy, the grandson of the rectory’s housekeeper, with whom he has a parental-like relationship, shakes everyone to their cores. I know it’s a cliche — family comes upon tragedy, novel unravels whether or not the accusations are true — but Haigh has a gift for character, and while this novel remains very traditional in its narrative format, I was impressed at how she tackled the subject matter. Haigh never shies away from the difficult nature of it, and I like how faith as a concept remains interwoven throughout the narrative. Arthur has never questioned his calling. But, like anyone, it’s impossible to know when something might happen to rock your beliefs, earthquake-like, and send you reeling in another direction. Innocent, even naive, to the ways of the world, Art finds himself questioning everything he has ever known: the church, his ministry, the idea of love, when he comes to face to face with Kath, the mother of the young boy he is accused of abusing. It takes the entire novel to truly find out what happened. And no one is left unscathed, not even the reader. Faith is a novel that forces one to evaluate one’s own relationship to God, to the church, even if you’re a non-believer. It’s impossible to stand in judgment, of anyone’s life, and I think that is the eloquent point that Haigh makes throughout this book. It’s one that definitely got me thinking. And I’m a girl who got the majority of her religious schooling from Are You There God, It’s Me Margaret? when she was a child. Of course, I read more widely about religion in university. (I still remember sitting with a particularly obnoxious Religion major at Queen’s who honestly said to me, “You know, it’s not as if I’m totally obsessed with God or anything, I just think Jesus was a really cool guy.” Seriously. That was her take on her entire degree. Good grief.) Regardless, the kind of storytelling that Haigh purports in this novel usually drives me crazy (the retelling of a story when one could choose just to tell the damn story) but it’s subtly balances nicely with the seriousness of the subject matter and I don’t think she could have written it another way. By the end, I was a little heartbroken, which, for me, is always the sign of a very good novel indeed.

#47 – Every Time We Say Goodbye by Jamie Zeppa

This is a Vicious Circle book club book, and I’m so pleased that I’ll get to discuss it with a great group of women. It’s a women’s novel (as you can see from the awful cover [I’m sorry but it really, really isn’t reflective of the book]) rather than dreamy chicklit as the cover suggests. I know what it’s going for — there’s a pair of siblings that the novel centres around, but the cover adds a layer of Hallmark Movie of the Week that dumbs down Zeppa’s sharp, instinctive and eager writing.

Told from multiple perspectives, the book follows three generations of Turner women, some blood, some married to blood, who each struggle with the idea of family, what it means to be a mother, and the difficult restrictions society, at different times over the last 50 years, for people of my gender. I fell particularly in love with Grace, a woman forced to leave her son behind to make a better life for herself in the city. Her strength, ability and the way she came into her own was particularly breathtaking. There’s a lot in the novel that isn’t necessarily fresh (troubled fathers, difficult women that seem cut from Lawrence, “women’s” troubles) but Zeppa finds a way in that is both refreshing and real — and I enjoyed this book immensely. I just have one tiny criticism — there’s a main character, Vera, a matriarchal figure, that we never hear from, she’s only portrayed through other people’s stories. I would have enjoyed knowing more about her point of view, her perspective, but I understand how too many voices could also ruin this novel. Regardless, it too is a perfect summer read. Funny how that works out, isn’t it?

Anyone who might dismiss Lynn Coady’s masterful Saints of Big Harbour as a regional novel would be selling themselves short, I think. Yes, it’s set in Nova Scotia in a small town adjunct to an even smaller hamlet where life resists any change that doesn’t first come in the form of a rumour; and yet, it’s as a pure novel that explores the ideas of love, life, and family as I’ve ever read anywhere. The whole book just swooped in and stole my heart.

Anyone who might dismiss Lynn Coady’s masterful Saints of Big Harbour as a regional novel would be selling themselves short, I think. Yes, it’s set in Nova Scotia in a small town adjunct to an even smaller hamlet where life resists any change that doesn’t first come in the form of a rumour; and yet, it’s as a pure novel that explores the ideas of love, life, and family as I’ve ever read anywhere. The whole book just swooped in and stole my heart.